Residence Museum > King’s Building – collections

Main information:

Residence Museum

The collections of the King’s Building: treasures from four centuries

In the rear section of the King’s Building (Königsbau) highlights and masterpieces from the Wittelsbachs’ former, abundantly stocked porcelain and silver chambers and their precious collection of miniatures are on display in over 20 exhibition rooms. These occupy a total of four floors behind the Nibelungen Halls and the royal apartments, with which they are directly connected via an internal staircase. They are accessed on the first upper floor via the Queen-Mother Staircase and the Antechamber in the Queen’s Apartment.

Silverware – Symbol of political power

The silver chamber in the Munich Residence is one of Europe’s largest remaining princely silver collections, comprising around 4,000 items. The collection, which mainly consists of tableware and utility articles, is an impressive record of aristocratic table culture through the centuries. Silverware, whether used for festive state banquets or intimate dinners, had always functioned in princely houses as a symbol of status, exclusivity and resplendence that reflected the resplendence of the dynasty. The gleaming products of the silver- and goldsmiths tell of banquets, precious gifts and acquisitions, which in times of peace decorated the tables of the electors and kings. The present inventory however also documents past periods of war and crisis, when the silver treasures were melted down to fill the state coffers with newly minted silver guilders.

During the Thirty Years’ War, much of Munich’s silver treasure was lost. However, later on the collection was expanded considerably with the silver belonging to the Palatinate Wittelsbachs, who ruled in Munich from 1777 as electors of Palatinate-Bavaria. In 1803 the comprehensive dinner service from the secularized prince-bishoprics of Bamberg and Würzburg was also added to the chamber.

Today the rich collections of the silver chamber are a record not only of the Wittelsbachs’ interest in the fashions of the day but also of the political history of Bavaria in the Early Modern Age.

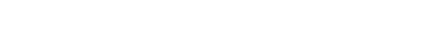

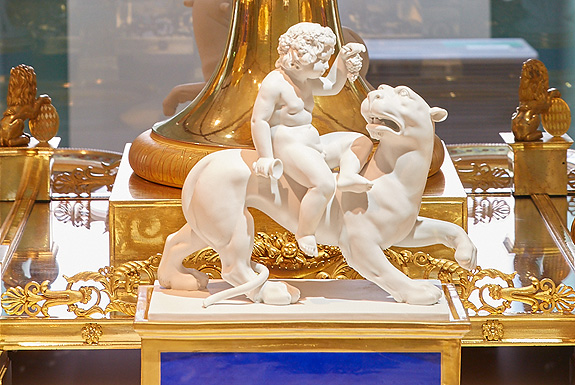

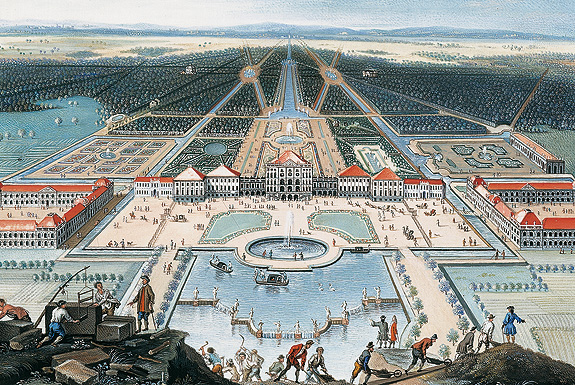

Porcelain of the 18th and 19th centuries – Triumph of a new art

The Wittelsbachs’ show collection of porcelain contains fantastic examples of the skills developed at the European porcelain manufactories in the 18th and 19th centuries: it was only in 1708 that ‘white gold’ was first successfully produced outside Asia. There was immediately an enormous demand for the new European porcelain at Europe’s courts. The manufactory in Meissen soon had competitors, who produced luxury goods of the highest quality as symbols of prestige for the rulers. From the mid-18th century on, the Wittelsbachs also had two such manufactories of their own in Nymphenburg and Frankenthal, and the best works from this source are now appropriately displayed in the new exhibition area. The Munich porcelain collection however contained not only local products, but also numerous diplomatic presents. Precious porcelain objects from the early years of the Meissen Manufactory, from Sèvres near Paris and the royal porcelain factory in Berlin were thus among the gifts to arrive at the Bavarian court. In the 19th century it was once again King Ludwig I who initiated an important development: he commissioned the Nymphenburg Manufactory to make artistically and technically remarkable copies of works from the royal collections, which still rank as masterpieces of European porcelain painting.

In this way a collection comprising many hundreds of individual items was assembled, which impressively documents not only the development of European porcelain art but also the changing international contacts between the politically and dynastically allied courts of Europe.

Princely tables – Table culture of the 18th and 19th centuries

Where the dining hall of the King’s Building was originally located before its destruction in 1944, tables sumptuously laid with silver and porcelain demonstrate the status-consciousness of the Wittelsbach rulers and their love of splendour, as well as their awareness of changing fashions and their considerable knowledge of art. Here visitors can see not only splendid, authentically arranged ensembles from the former electoral-royal porcelain and silver chambers but also the sophisticated symbolism of the complex princely dining ceremony that continued into the 19th century, and the enormous material expenditure and artistic effort required to maintain it.

Among the highlights of the exhibition are the magnificent porcelain service that the Berlin court sent to Munich in 1842 as a wedding present for the Bavarian crown prince Maximilian and his bride Marie of Prussia, and the comprehensive silver-gilded dining service of King Max I Joseph. This outstanding Neoclassical ensemble was originally made in 1807-1809 by the Paris goldsmiths Martin-Guillaume Biennais and Jean-Baptiste-Claude Odiot for King Jérôme of Westphalia, the brother of Emperor Napoleon. It was acquired shortly afterwards by the Bavarian court.

Miniature paintings – Magical worlds on a tiny scale

The collection of miniatures in the Residence is one of the most important of its kind in existence. It comprises a broad spectrum of miniatures spanning a period from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The beautiful tiny paintings, many of which would fit into the palm of a hand, show detailed landscapes, charming portraits, mythological and Biblical scenes and witty allegories.

The origins of miniature painting lie in medieval book illumination. With the advent of printed books, it became an independent art form, painted on parchment, enamel or precious ivory. Miniatures were thus greatly in demand, both as collector’s items – painting collections in miniature – and ‘intimate works of art’ preserving the memory of loved persons in small portraits. The new exhibition offers visitors the opportunity to examine these tiny treasures in detail and explore their various functions and the contexts that produced them.

In addition to the collections presented here, the following collections are also worth a visit:

Reliquaries – Mystical creations in gold and crystal

East Asian Collection – Fragile treasures from the other side of the world.

Facebook Instagram YouTube